4n6ir.com

CCM_RecentlyUsedApps Update on Unicode Strings

by James Habben

The research and development that I did previously for the CCM_RecentlyUsedApps record structure and EnScript carving tool was done against case data I was using during investigations. Unfortunately, I had no data available with any of the string data having been written in Unicode characters. With the thought that Windows has been designed with international languages in mind, I used the UTF8 codepage when reading to hopefully catch any switch to Unicode type characters. Using UTF8 is a very safe alternative to ASCII because it defaults to plain ASCII in the lower ranges, and starts expanding bytes when it gets higher. I have an update, however, because I got a volunteer from twitter to graciously do some testing. Thanks @MattNels for the help!

The Tests

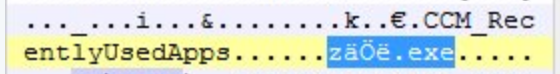

The first test that he ran was using characters that were not in the standard ASCII range. The characters like ä or ö are latin based characters with the umlaut dots above, and they fall within the scope of ASCII when you include both the low and the high ranges.

He created a testing directory on his system, which is under the management of his company’s SCCM deployment services. If you recall from my prior posts on this subject, this artifact is triggered simply by being a member. In this directory, he renamed an executable to include the above mention characters from the high ASCII range. The result show that the record stored those high characters exactly the same as the low range characters. You can see what that looks like in the following image.

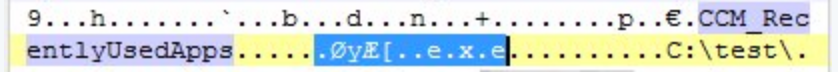

The next test he ran was to rename that executable again to something high enough in the Unicode range to get clear of the ASCII characters. He went with “秘密”, which consists of two glyphs 0x79d8 and 0x5bc6. Keeping in mind our CPU architecture, we know that those bytes have to be swapped when written to disk as Unicode characters. The text would translate to four bytes on disk as: d8 79 c6 5b.

Another option, going with my earlier assumption/guess, is for the string to be written using UTF8. The use of UTF8 is pretty common on OS X, and less common on Windows, from my experience. Nevertheless, it would be worth being prepared to see what the bytes would look like if it was UTF8. The above glyphs translate into six bytes on disk, three for each character, but we don’t swap the bytes around like we did with Unicode. Confusing, right? Anyways, those bytes would look like this on disk: E7 A7 98 E5 AF 86.

Drumroll please…

The result was evidence of switching to Unicode. You can immediately recognize it as Unicode because of the 0x00 bytes between the extension “.exe” of that file. If you use a hex->ASCII converter on the Unicode bytes from above (d8 79 c6 5b) you get back “ØyÆ[“, which lines up nicely with the following image.

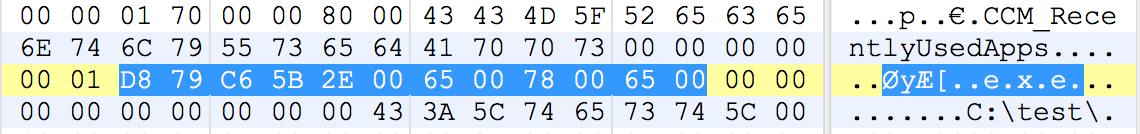

Now you ask: How do we programmatically determine if the string was written using Unicode or ASCII? Excellent question, and I am glad that you are tracking with me!

Let’s expand the view of this record a bit, and recall the structure of the format from the last post. The strings in Windows are typically followed with a 0x00 (null) byte to indicate where the string data stops. It is referred to as C style strings because this is how the C programming language stores strings in memory. In this record however, the strings were separated byte two 0x00 bytes. Take a close look at the following image of the expanded record with the Unicode string.

Did you spot the indicator? Look again at the byte immediately preceding the highlighted string data, and you will see that it is a 0x01 value. This byte has been a 0x00 value in all of my testing because I didn’t have any strings with Unicode text in them, or at least not to my knowledge. Since executables need to have these latin based extensions, the property will actually look to be ending with three 0x00 bytes. The first of those is actually part of the preceding ‘e’. Since this string has been written entirely in Unicode, the null terminating character mentioned just above gets expanded as well. The next byte is then either a 0x00 or 0x01 indicating the codepage for the next string property.

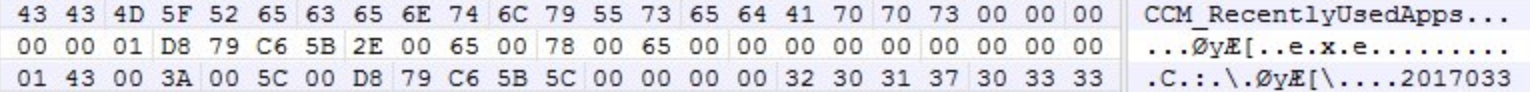

An interesting side note on a situation that Matt ran into, the use of the path “c:\test2\秘密\秘密.exe” for the executable resulted in no records indicating execution. He ran a number of tests surrounding that scenario, and there is something about that path that prevents the recording.

He continued with changing the path to “c:\秘密\秘密.exe”, and the artifact was back. We wanted to get confirmation of that 0x01 indicator byte using another string value. Sure enough, we got it in the following image.

Tool Update

The EnScript that I wrote to carve and parse these records</a> has been updated to properly look for the 0x00 and 0x01 bytes indicating ASCII or Unicode usage. Please reach out to me if you find any problems or have any questions.

Additionally, Matt is adding this artifact to his irFARTpull collection PowerShell. These artifacts can be collected by having PowerShell perform a WMI query against the namespace and class where these records are stored. It should look something like this:

https://github.com/n3l5/irFARTpull

Get-WmiObject -namespace root\ccm\SoftwareMeteringAgent -class CCM_RecentlyUsedApps

Lessons Learned

This is a perfect example of being aware of what your tools are doing behind the scenes and always validating and testing them. Many of the artifacts that we search for and use to show patterns of behavior are detailed through reverse engineering. This process can be helpful, but it can also be a bit blind in not being able to analyze what we don’t have available.

If you aren’t a programmer, you can still contribute with testing, or even just thoughts on possible scenarios of failure. Hopefully the authors of the tools out there will be accepting of the feedback, as it will only provide more benefit for the community.

James Habben

tags: Prefetch