4n6ir.com

GUIs are Hard - Python to the Rescue - Part 1

by James Habben

I consider myself an equal opportunity user of tools, but in the same respect I am also an equal opportunity critic of tools. There are both commercial and open source digital forensic and security tools that do a lot of things well, and a lot of things not so well. What makes for a good DFIR examiner is the ability to sort through the marketing fluff to learn what these tools can truly do and also figure out what they can do very well.

One of the things that I find limiting in many of the tools is the Graphical User Interface (GUI). We deal with a huge amount of data, and we sometimes analyze it in ways we couldn’t have predicted ourselves. GUI tools make a lot of tasks easy, but they can also make some of the simplest tasks seem impossible.

My recommendation? Every tool should offer output in a few formats: CSV, JSON, SQLite. Give me the ability to go primal!

Tool of the Day

I have had a number of cases lately that have started as ‘malware’ cases. Evil traffic tripped an alarm, and that means there must be malware on the disk. It shouldn’t be surprising to you, as a DFIR examiner, that this is not always the case. Sometimes there is a bonehead user browsing stupid websites.

Internet Evidence Finder (IEF) is the best tool I have available right now to parse and carve the broad variety of internet activity artifacts from the drive images. It does a pretty good job searching over the disk to find browser, web app, and website artifacts (though I don’t know exactly which versions are supported due to documentation, but I will digress in a different post).

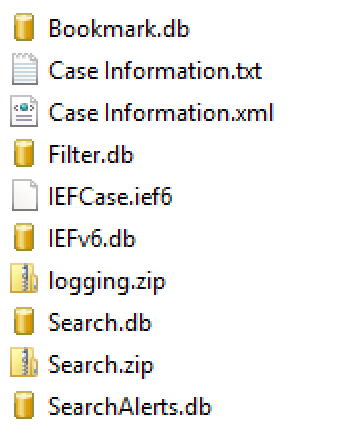

Let me cover some of IEF’s basic storage structure that I have worked out first. The artifacts are stored in SQLite format in the folder that you designate, and it is named ‘IEFv6.db’. Every artifact type that is found creates at least one table in the DB. Because each artifact has different properties, each of the tables have a different schema. Some good things that the dev team at Magnet seem to have decided on do allow for some kind of consistency. If the column has URL data in it, then the column name has ‘URL’ in it. Similarly for dates, the column name will have ‘date’ in it.

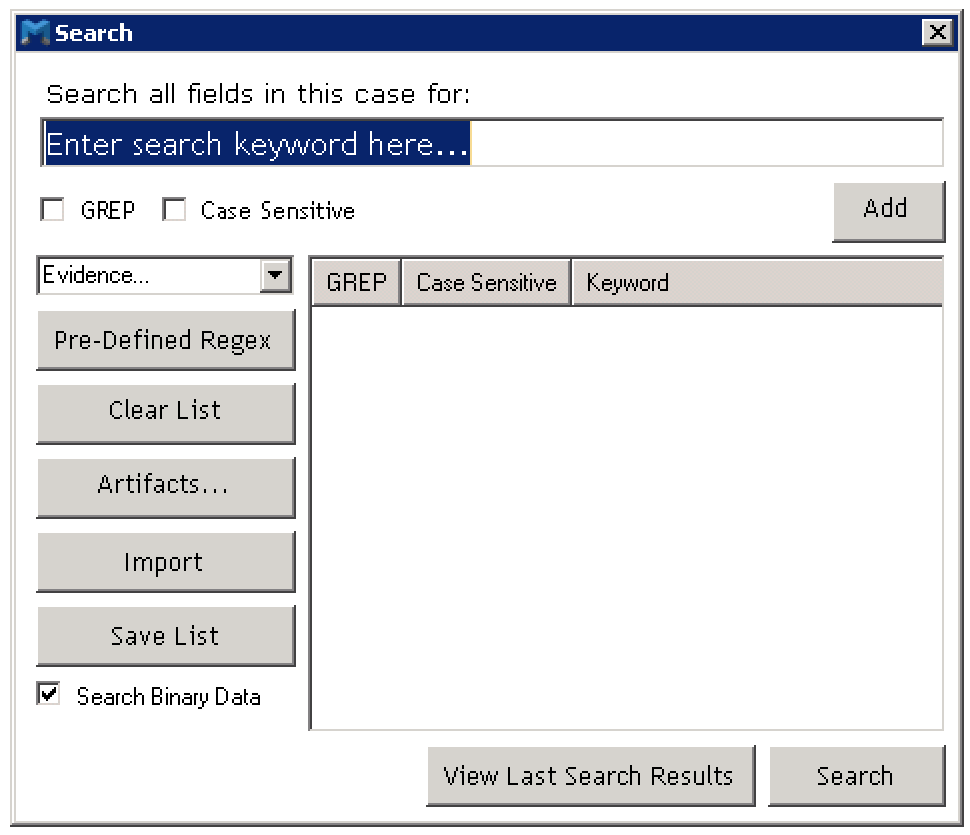

IEF provides a search function that allows you to do some basic string searching, or you can get a bit more advanced by providing a RegEx (GREP) pattern for the search. When you kick off this search, IEF creates a new SQLite db file named ‘Search.db’ and it is stored in the same folder. You can only have one search completed at a time since kicking off a new search will cause IEF to overwrite any previous db that was created. The search db, from what i can tell anyways, seems to have an identical schema structure as the main db, only it has been filtered down on the number of records that it holds based on the keywords or patterns that you provided.

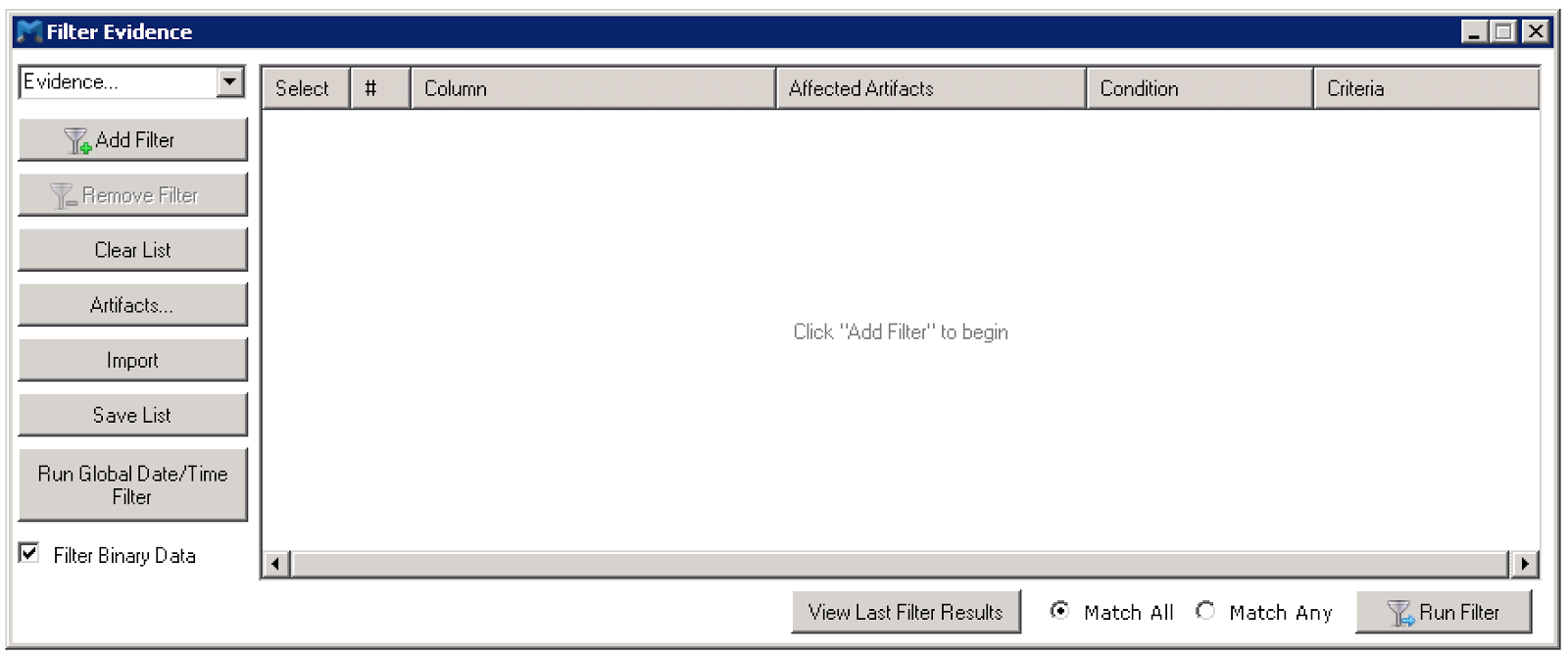

There is another feature called filter, and I will admit that I have only recently found this. It allows you to apply various criteria to the dataset, with the major one being a date range. There are other things you can filter one, but I haven’t needed to explore those just yet. When you kick off this process, you end up with yet another SQLite database filled with a reduced number of records based on the criteria and again it seems identical in schema as the main db. This one is named ‘filter.db’ and indicates that the dev team doesn’t have much creativity. ;)

Problem of the Month

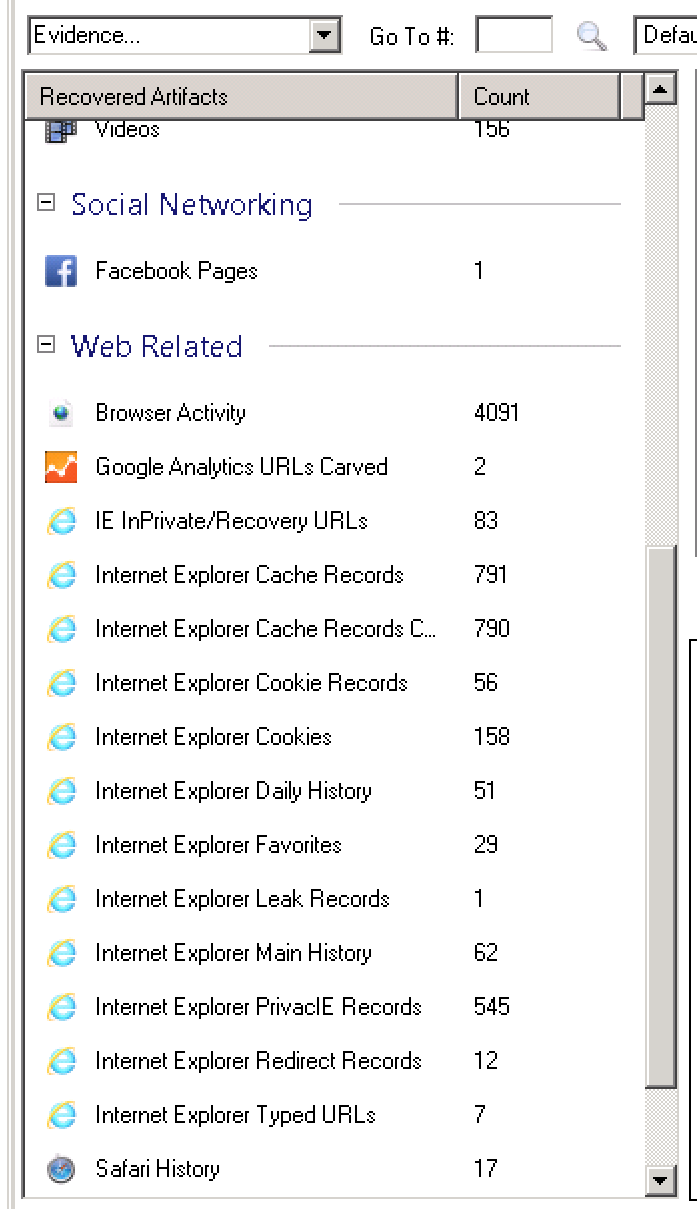

The major issue I have with the tool is in the way it presents data to me. The interface has a great way of digging into forensic artifacts as they are categorized and divided by the artifact type. You can dig into the nitty gritty details of each browser artifact. For the cases that I have used IEF for lately, and I suspect many of you in your Incident Response cases as well, I really don’t actually care which browser was the source of the traffic. I just need to know if that URL was browsed by bonehead so I can get him fired and move on. Too harsh? :)

IEF doesn’t give you the ability to have a view where all of the URLs are consolidated. You have to click, click, click down through the many artifacts, and look through tons of duplicate URLs. The problem behind this is on the design of the artifact storage in multiple tables with different schemas in a relational database. A document based database, such as MongoDB, would have provided an easier search approach, but there are trade-offs that I don’t need to tangent on here. I will just say that there is no 100% clear winner.

To perform a search over multiple tables in a SQL based DB, you have to implement it in some kind of program code because a SQL query is almost impossible to construct. SQLite makes it even more difficult with its reduced list of native functions and it’s lack of ability to create any user-defined functions or stored procedures. It just wasn’t meant for that. IEF handles this task for the search and filter process in c# code, and creates those new DB files as a sort of cache mechanism.

Solution of the Year

Alright, I am sensationalizing my own work a bit too much, but it is easy to do when it makes your work so much easier. That is the case with the python script I am showing you here. It was born out of necessity and tweaked to meet my needs for different cases. This one has saved me a lot of time, and I want to share it with you.

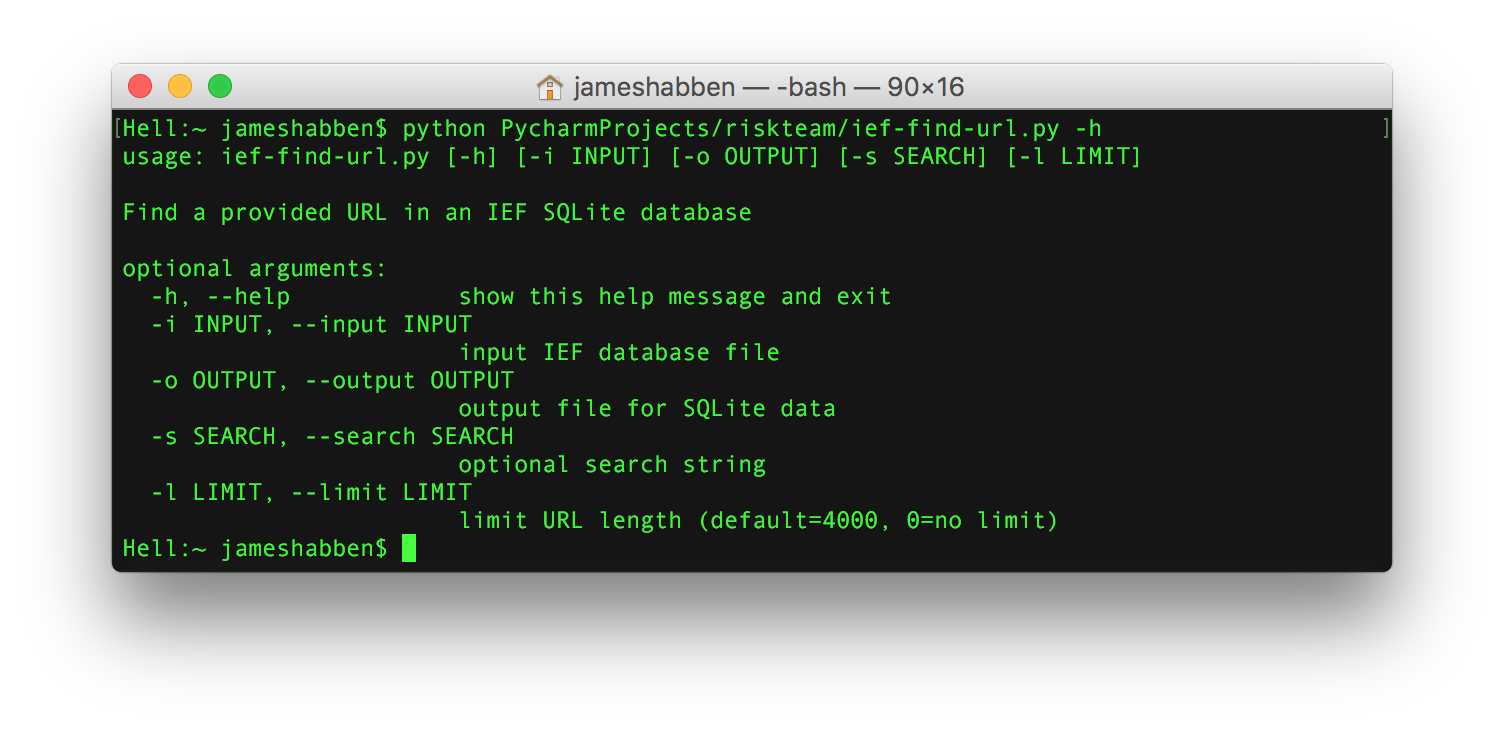

This python script can take an input (-i) of any 3 of the IEF database files that I mentioned above since they share schema structures. The output (-o) is another SQLite database file (I know, like you need another one in addition) in the location of your choosing.

The search (-s) parameter allow you to provide a string to filter the records on based upon that string being present in one of the URL fields of the record being transferred. I added this one because the search function of IEF doesn’t allow me to direct the keyword at a URL field. I had results from my keywords that were hitting on several other metadata fields that I had no interest in.

The limit (-l) parameter was added because of a bug I found in IEF with some of the artifacts. I think it was mainly in the carved artifacts so I really can’t fault too much, but it was causing a size and time issue for me. The bug is that the URL field for a number of records was pushing over 3 million characters long. Let me remind you that each character in ASCII is a byte, and having 3 million of those creates a URL that is 3 megabytes in size. Keep in mind that URLs are allowed to be Unicode, so go ahead and x2 that. I found that most browsers start choking if you give them a URL over 2000 characters, so I decided to cutoff the URL field at 4000 by default to give just a little wiggle room. Magnet is aware of this and will hopefully solve the issue in an upcoming version.

This python script will open the IEF DB file and work its way through each of the tables to look for any columns that have ‘URL’ in the name. If one is found, it will grab the type of the artifact and the value of the URL to create a new record in the new DB file. Some of the records in the IEF artifacts have multiple URL fields, and this will take each one of them into the new file as a simple URL value. The source column is the name of the table (artifact type) and the name of the column of where that value came from.

This post has gotten rather long, so this will be the end of part 1. In part 2, I will go through the new DB structure to explain the SQL views that are created and then walk through some of the code in Python to see how things are done.

In the meantime, you can download the ief-find-url.py Python script and take a look for yourself. You will have to supply your own IEF.

https://github.com/JamesHabben/HelpfulPython/blob/master/ief-find-url.py

James Habben

tags: Python